Evolution

and the Origins of Disease

The principles of

evolution by natural selection are finally beginning to inform medicine by

Randolph M. Nesse and George C. Williams ...........

Thoughtful

contemplation of the human body elicits awe--in equal measure with perplexity.

The eye, for instance, has long been an object of wonder, with the clear,

living tissue of the cornea curving just the right amount, the iris adjusting

to brightness and the lens to distance, so that the optimal quantity of light focuses

exactly on the surface of the retina. Admiration of such apparent perfection

soon gives way, however, to consternation. Contrary to any sensible design,

blood vessels and nerves traverse the inside of the retina, creating a blind

spot at their point of exit.

The body is a

bundle of such jarring contradictions. For each exquisite heart valve, we have

a wisdom tooth. Strands of DNA direct the development of the 10 trillion cells

that make up a human adult but then permit his or her steady deterioration and

eventual death. Our immune system can identify and destroy a million kinds of

foreign matter, yet many bacteria can still kill us. These contradictions make

it appear as if the body was designed by a team of superb engineers with

occasional interventions by Rube Goldberg.

In fact, such

seeming incongruities make sense but only when we investigate the origins of

the body's vulnerabilities while keeping in mind the wise words of

distinguished geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky: "Nothing in biology makes sense

except in the light of evolution." Evolutionary biology is, of course, the

scientific foundation for all biology, and biology is the foundation for all

medicine. To a surprising degree, however, evolutionary biology is just now

being recognized as a basic medical science. The enterprise of studying medical

problems in an evolutionary context has been termed Darwinian medicine. Most

medical research tries to explain the causes of an individual's disease and

seeks therapies to cure or relieve deleterious conditions. These efforts are

traditionally based on consideration of proximate issues, the straightforward

study of the body's anatomic and physiological mechanisms as they currently

exist. In contrast, Darwinian medicine asks why the body is designed in a way

that makes us all vulnerable to problems like cancer, atherosclerosis,

depression and choking, thus offering a broader context in which to conduct

research.

DEFENSIVE

RESPONSES

The evolutionary

explanations for the body's flaws fall into surprisingly few categories. First,

some discomforting conditions, such as pain, fever, cough, vomiting and

anxiety, are actually neither diseases nor design defects but rather are

evolved defenses. Second, conflicts with other organisms--Escherichia coli or crocodiles,

for instance--are a fact of life. Third, some circumstances, such as the ready

availability of dietary fats, are so recent that natural selection has not yet

had a chance to deal with them. Fourth, the body may fall victim to trade-offs

between a trait's benefits and its costs; a textbook example is the sickle cell

gene, which also protects against malaria. Finally, the process of natural

selection is constrained in ways that leave us with suboptimal design features,

as in the case of the mammalian eye.

Evolved Defenses

Perhaps the most

obviously useful defense mechanism is coughing; people who cannot clear foreign

matter from their lungs are likely to die from pneumonia. The capacity for pain

is also certainly beneficial. The rare individuals who cannot feel pain fail

even to experience discomfort from staying in the same position for long

periods. Their unnatural stillness impairs the blood supply to their joints,

which then deteriorate. Such pain-free people usually die by early adulthood from

tissue damage and infections. Cough or pain is usually interpreted as disease

or trauma but is actually part of the solution rather than the problem. These

defensive capabilities, shaped by natural selection, are kept in reserve until

needed.

Less widely

recognized as defenses are fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anxiety, fatigue,

sneezing and inflammation. Even some physicians remain unaware of fever's

utility. No mere increase in metabolic rate, fever is a carefully regulated

rise in the set point of the body's thermostat. The higher body temperature

facilitates the destruction of pathogens. Work by Matthew J. Kluger of the

Lovelace Institute in Albuquerque, N.M., has shown that even cold-blooded

lizards, when infected, move to warmer places until their bodies are several

degrees above their usual temperature. If prevented from moving to the warm

part of their cage, they are at increased risk of death from the infection. In

a similar study by Evelyn Satinoff of the University of Delaware, elderly rats,

who can no longer achieve the high fevers of their younger lab companions, also

instinctively sought hotter environments when challenged by infection.

A reduced level

of iron in the blood is another misunderstood defense mechanism. People

suffering from chronic infection often have decreased levels of blood iron.

Although such low iron is sometimes blamed for the illness, it actually is a

protective response: during infection, iron is sequestered in the liver, which

prevents invading bacteria from getting adequate supplies of this vital

element.

Morning sickness

has long been considered an unfortunate side effect of pregnancy. The nausea,

however, coincides with the period of rapid tissue differentiation of the

fetus, when development is most vulnerable to interference by toxins. And

nauseated women tend to restrict their intake of strong-tasting, potentially

harmful substances. These observations led independent researcher Margie Profet

to hypothesize that the nausea of pregnancy is an adaptation whereby the mother

protects the fetus from exposure to toxins. Profet tested this idea by

examining pregnancy outcomes. Sure enough, women with more nausea were less

likely to suffer miscarriages. (This evidence supports the hypothesis but is

hardly conclusive. If Profet is correct, further research should discover that

pregnant females of many species show changes in food preferences. Her theory

also predicts an increase in birth defects among offspring of women who have

little or no morning sickness and thus eat a wider variety of foods during

pregnancy.)

Another common

condition, anxiety, obviously originated as a defense in dangerous situations

by promoting escape and avoidance. A 1992 study by Lee A. Dugatkin of the

University of Louisville evaluated the benefits of fear in guppies. He grouped

them as timid, ordinary or bold, depending on their reaction to the presence of

smallmouth bass. The timid hid, the ordinary simply swam away, and the bold

maintained their ground and eyed the bass. Each guppy group was then left alone

in a tank with a bass. After 60 hours, 40 percent of the timid guppies had

survived, as had only 15 percent of the ordinary fish. The entire complement of

bold guppies, on the other hand, wound up aiding the transmission of bass genes

rather than their own.

Selection for

genes promoting anxious behaviors implies that there should be people who

experience too much anxiety, and indeed there are. There should also be

hypophobic individuals who have insufficient anxiety, either because of genetic

tendencies or antianxiety drugs. The exact nature and frequency of such a

syndrome is an open question, as few people come to psychiatrists complaining

of insufficient apprehension. But if sought, the pathologically nonanxious may

be found in emergency rooms, jails and unemployment lines.

The utility of

common and unpleasant conditions such as diarrhea, fever and anxiety is not

intuitive. If natural selection shapes the mechanisms that regulate defensive

responses, how can people get away with using drugs to block these defenses

without doing their bodies obvious harm? Part of the answer is that we do, in

fact, sometimes do ourselves a disservice by disrupting defenses.

Herbert L. DuPont

of the University of Texas at Houston and Richard B. Hornick of Orlando

Regional Medical Center studied the diarrhea caused by Shigella infection and

found that people who took antidiarrhea drugs stayed sick longer and were more

likely to have complications than those who took a placebo. In another example,

Eugene D. Weinberg of Indiana University has documented that well-intentioned

attempts to correct perceived iron deficiencies have led to increases in

infectious disease, especially amebiasis, in parts of Africa. Although the iron

in most oral supplements is unlikely to make much difference in otherwise

healthy people with everyday infections, it can severely harm those who are

infected and malnourished. Such people cannot make enough protein to bind the

iron, leaving it free for use by infectious agents.

On the

morning-sickness front, an antinausea drug was recently blamed for birth

defects. It appears that no consideration was given to the possibility that the

drug itself might be harmless to the fetus but could still be associated with

birth defects, by interfering with the mother's defensive nausea.

Another obstacle

to perceiving the benefits of defenses arises from the observation that many

individuals regularly experience seemingly worthless reactions of anxiety,

pain, fever, diarrhea or nausea. The explanation requires an analysis of the

regulation of defensive responses in terms of signal-detection theory. A

circulating toxin may come from something in the stomach. An organism can expel

it by vomiting, but only at a price. The cost of a false alarm--vomiting when

no toxin is truly present--is only a few calories. But the penalty for a single

missed authentic alarm--failure to vomit when confronted with a toxin--may be

death.

Natural selection

therefore tends to shape regulation mechanisms with hair triggers, following

what we call the smoke-detector principle. A smoke alarm that will reliably

wake a sleeping family in the event of any fire will necessarily give a false

alarm every time the toast burns. The price of the human body's numerous

"smoke alarms" is much suffering that is completely normal but in

most instances unnecessary. This principle also explains why blocking defenses

is so often free of tragic consequences. Because most defensive reactions occur

in response to insignificant threats, interference is usually harmless; the

vast majority of alarms that are stopped by removing the battery from the smoke

alarm are false ones, so this strategy may seem reasonable. Until, that is, a

real fire occurs.

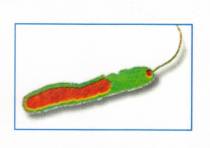

Conflicts with

Other Organisms

Natural selection

is unable to provide us with perfect protection against all pathogens, because

they tend to evolve much faster than humans do. E. coli, for example, with its

rapid rates of reproduction, has as much opportunity for mutation and selection

in one day as humanity gets in a millennium. And our defenses, whether natural

or artificial, make for potent selection forces. Pathogens either quickly

evolve a counterdefense or become extinct. Amherst College biologist Paul W.

Ewald has suggested classifying phenomena associated with infection according

to whether they benefit the host, the pathogen, both or neither. Consider the

runny nose associated with a cold. Nasal mucous secretion could expel

intruders, speed the pathogen's transmission to new hosts or both [see

"The Evolution of Virulence," by Paul W. Ewald; Scientific American,

April 1993]. Answers could come from studies examining whether blocking nasal

secretions shortens or prolongs illness, but few such studies have been done.

EVOLUTION

OF VIRULENCE

Humanity won huge

battles in the war against pathogens with the development of antibiotics and

vaccines. Our victories were so rapid and seemingly complete that in 1969 U.S.

Surgeon General William H. Stewart said that it was "time to close the

book on infectious disease." But the enemy, and the power of natural

selection, had been underestimated. The sober reality is that pathogens

apparently can adapt to every chemical researchers develop. ("The war has

been won," one scientist more recently quipped. "By the other

side.")

Antibiotic

resistance is a classic demonstration of natural selection. Bacteria that

happen to have genes that allow them to prosper despite the presence of an

antibiotic reproduce faster than others, and so the genes that confer resistance

spread quickly. As shown by Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg of the Rockefeller

University, they can even jump to different species of bacteria, borne on bits

of infectious DNA. Today some strains of tuberculosis in New York City are

resistant to all three main antibiotic treatments; patients with those strains

have no better chance of surviving than did TB patients a century ago. Stephen

S. Morse of Columbia University notes that the multidrug-resistant strain that

has spread throughout the East Coast may have originated in a homeless shelter

across the street from Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. Such a phenomenon

would indeed be predicted in an environment where fierce selection pressure

quickly weeds out less hardy strains. The surviving bacilli have been bred for

resistance.

Many people,

including some physicians and scientists, still believe the outdated theory

that pathogens necessarily become benign after long association with hosts.

Superficially, this makes sense. An organism that kills rapidly may never get

to a new host, so natural selection would seem to favor lower virulence.

Syphilis, for instance, was a highly virulent disease when it first arrived in

Europe, but as the centuries passed it became steadily more mild. The virulence

of a pathogen is, however, a life history trait that can increase as well as

decrease, depending on which option is more advantageous to its genes.

For agents of

disease that are spread directly from person to person, low virulence tends to

be beneficial, as it allows the host to remain active and in contact with other

potential hosts. But some diseases, like malaria, are transmitted just as

well--or better--by the incapacitated. For such pathogens, which usually rely

on intermediate vectors like mosquitoes, high virulence can give a selective

advantage. This principle has direct implications for infection control in

hospitals, where health care workers' hands can be vectors that lead to

selection for more virulent strains.

In the case of

cholera, public water supplies play the mosquitoes' role. When water for

drinking and bathing is contaminated by waste from immobilized patients,

selection tends to increase virulence, because more diarrhea enhances the

spread of the organism even if individual hosts quickly die. But, as Ewald has

shown, when sanitation improves, selection acts against classical Vibrio

cholerae bacteria in favor of the more benign El Tor biotype. Under these

conditions, a dead host is a dead end. But a less ill and more mobile host,

able to infect many others over a much longer time, is an effective vehicle for

a pathogen of lower virulence. In another example, better sanitation leads to

displacement of the aggressive Shigella flexneri by the more benign S. sonnei.

NEW

ENVIRONMENTS, NEW THREATS

Such

considerations may be relevant for public policy. Evolutionary theory predicts

that clean needles and the encouragement of safe sex will do more than save

numerous individuals from HIV infection. If humanity's behavior itself slows

HIV transmission rates, strains that do not soon kill their hosts have the

long-term survival advantage over the more virulent viruses that then die with

their hosts, denied the opportunity to spread. Our collective choices can

change the very nature of HIV.

Conflicts with

other organisms are not limited to pathogens. In times past, humans were at

great risk from predators looking for a meal. Except in a few places, large

carnivores now pose no threat to humans. People are in more danger today from

smaller organisms' defenses, such as the venoms of spiders and snakes.

Ironically, our fears of small creatures, in the form of phobias, probably

cause more harm than any interactions with those organisms do. Far more

dangerous than predators or poisoners are other members of our own species. We

attack each other not to get meat but to get mates, territory and other

resources. Violent conflicts between individuals are overwhelmingly between

young men in competition and give rise to organizations to advance these aims.

Armies, again usually composed of young men, serve similar objectives, at huge

cost.

Even the most

intimate human relationships give rise to conflicts having medical

implications. The reproductive interests of a mother and her infant, for

instance, may seem congruent at first but soon diverge. As noted by biologist

Robert L. Trivers in a now classic 1974 paper, when her child is a few years

old, the mother's genetic interests may be best served by becoming pregnant

again, whereas her offspring benefits from continuing to nurse. Even in the

womb there is contention. From the mother's vantage point, the optimal size of

a fetus is a bit smaller than that which would best serve the fetus and the

father. This discord, according to David Haig of Harvard University, gives rise

to an arms race between fetus and mother over her levels of blood pressure and

blood sugar, sometimes resulting in hypertension and diabetes during pregnancy.

Coping with

Novelty

Making rounds in

any modern hospital provides sad testimony to the prevalence of diseases

humanity has brought on itself. Heart attacks, for example, result mainly from

atherosclerosis, a problem that became widespread only in this century and that

remains rare among hunter-gatherers. Epidemiological research furnishes the

information that should help us prevent heart attacks: limit fat intake, eat

lots of vegetables, and exercise hard each day. But hamburger chains

proliferate, diet foods languish on the shelves, and exercise machines serve as

expensive clothing hangers throughout the land. The proportion of overweight

Americans is one third and rising. We all know what is good for us. Why do so

many of us continue to make unhealthy choices?

Our poor

decisions about diet and exercise are made by brains shaped to cope with an

environment substantially different from the one our species now inhabits. On

the African savanna, where the modern human design was fine-tuned, fat, salt

and sugar were scarce and precious. Individuals who had a tendency to consume

large amounts of fat when given the rare opportunity had a selective advantage.

They were more likely to survive famines that killed their thinner companions.

And we, their descendants, still carry those urges for foodstuffs that today

are anything but scarce. These evolved desires--inflamed by advertisements from

competing food corporations that themselves survive by selling us more of

whatever we want to buy--easily defeat our intellect and willpower. How ironic

that humanity worked for centuries to create environments that are almost

literally flowing with milk and honey, only to see our success responsible for

much modern disease and untimely death.

Increasingly,

people also have easy access to many kinds of drugs, especially alcohol and

tobacco, that are responsible for a huge proportion of disease, health care

costs and premature death. Although individuals have always used psychoactive

substances, widespread problems materialized only following another

environmental novelty: the ready availability of concentrated drugs and new,

direct routes of administration, especially injection. Most of these

substances, including nicotine, cocaine and opium, are products of natural

selection that evolved to protect plants from insects. Because humans share a

common evolutionary heritage with insects, many of these substances also affect

our nervous system.

This perspective

suggests that it is not just defective individuals or disordered societies that

are vulnerable to the dangers of psychoactive drugs; all of us are susceptible

because drugs and our biochemistry have a long history of interaction.

Understanding the details of that interaction, which is the focus of much

current research from both a proximate and evolutionary perspective, may well

lead to better treatments for addiction.

The relatively

recent and rapid increase in breast cancer must be the result in large part of

changing environments and ways of life, with only a few cases resulting solely

from genetic abnormalities. Boyd Eaton and his colleagues at Emory University

reported that the rate of breast cancer in today's "nonmodern"

societies is only a tiny fraction of that in the U.S. They hypothesize that the

amount of time between menarche and first pregnancy is a crucial risk factor,

as is the related issue of total lifetime number of menstrual cycles. In

hunter-gatherers, menarche occurs at about age 15 or later, followed within a

few years by pregnancy and two or three years of nursing, then by another

pregnancy soon after. Only between the end of nursing and the next pregnancy

will the woman menstruate and thus experience the high levels of hormones that

may adversely affect breast cells.

In modern

societies, in contrast, menarche occurs at age 12 or 13--probably at least in

part because of a fat intake sufficient to allow an extremely young woman to

nourish a fetus--and the first pregnancy may be decades later or never. A

female hunter-gatherer may have a total of 150 menstrual cycles, whereas the

average woman in modern societies has 400 or more. Although few would suggest

that women should become pregnant in their teens to prevent breast cancer

later, early administration of a burst of hormones to simulate pregnancy may

reduce the risk. Trials to test this idea are now under way at the University

of California at San Diego.

Trade-offs and

Constraints

Compromise is

inherent in every adaptation. Arm bones three times their current thickness

would almost never break, but Homo sapiens would be lumbering creatures on a

never-ending quest for calcium. More sensitive ears might sometimes be useful,

but we would be distracted by the noise of air molecules banging into our

eardrums.

Such trade-offs

also exist at the genetic level. If a mutation offers a net reproductive

advantage, it will tend to increase in frequency in a population even if it

causes vulnerability to disease. People with two copies of the sickle cell

gene, for example, suffer terrible pain and die young. People with two copies

of the "normal" gene are at high risk of death from malaria. But individuals

with one of each are protected from both malaria and sickle cell disease. Where

malaria is prevalent, such people are fitter, in the Darwinian sense, than

members of either other group. So even though the sickle cell gene causes

disease, it is selected for where malaria persists. Which is the

"healthy" allele in this environment? The question has no answer.

There is no one normal human genome--there are only genes.

SMALL

APPENDIX

Many other genes

that cause disease must also have offered benefits, at least in some

environments, or they would not be so common. Because cystic fibrosis (CF)

kills one out of 2,500 Caucasians, the responsible genes would appear to be at

great risk of being eliminated from the gene pool. And yet they endure. For years,

researchers mused that the CF gene, like the sickle cell gene, probably

conferred some advantage. Recently a study by Gerald B. Pier of Harvard Medical

School and his colleagues gave substance to this informed speculation: having

one copy of the CF gene appears to decrease the chances of the bearer acquiring

a typhoid fever infection, which once had a 15 percent mortality.

Aging may be the

ultimate example of a genetic trade-off. In 1957 one of us (Williams) suggested

that genes that cause aging and eventual death could nonetheless be selected

for if they had other effects that gave an advantage in youth, when the force

of selection is stronger. For instance, a hypothetical gene that governs

calcium metabolism so that bones heal quickly but that also happens to cause

the steady deposition of calcium in arterial walls might well be selected for

even though it kills some older people. The influence of such pleiotropic genes

(those having multiple effects) has been seen in fruit flies and flour beetles,

but no specific example has yet been found in humans. Gout, however, is of

particular interest, because it arises when a potent antioxidant, uric acid,

forms crystals that precipitate out of fluid in joints. Antioxidants have

antiaging effects, and plasma levels of uric acid in different species of

primates are closely correlated with average adult life span. Perhaps high

levels of uric acid benefit most humans by slowing tissue aging, while a few

pay the price with gout.

Other examples

are more likely to contribute to more rapid aging. For instance, strong immune

defenses protect us from infection but also inflict continuous, low-level

tissue damage. It is also possible, of course, that most genes that cause aging

have no benefit at any age--they simply never decreased reproductive fitness

enough in the natural environment to be selected against. Nevertheless, over

the next decade research will surely identify specific genes that accelerate

senescence, and researchers will soon thereafter gain the means to interfere

with their actions or even change them. Before we tinker, however, we should

determine whether these actions have benefits early in life.

Because evolution

can take place only in the direction of time's arrow, an organism's design is

constrained by structures already in place. As noted, the vertebrate eye is

arranged backward. The squid eye, in contrast, is free from this defect, with

vessels and nerves running on the outside, penetrating where necessary and

pinning down the retina so it cannot detach. The human eye's flaw results from

simple bad luck; hundreds of millions of years ago, the layer of cells that

happened to become sensitive to light in our ancestors was positioned

differently from the corresponding layer in ancestors of squids. The two

designs evolved along separate tracks, and there is no going back.

Such path

dependence also explains why the simple act of swallowing can be

life-threatening. Our respiratory and food passages intersect because in an

early lungfish ancestor the air opening for breathing at the surface was

understandably located at the top of the snout and led into a common space

shared by the food passageway. Because natural selection cannot start from

scratch, humans are stuck with the possibility that food will clog the opening

to our lungs.

The path of

natural selection can even lead to a potentially fatal cul-de-sac, as in the

case of the appendix, that vestige of a cavity that our ancestors employed in

digestion. Because it no longer performs that function, and as it can kill when

infected, the expectation might be that natural selection would have eliminated

it. The reality is more complex. Appendicitis results when inflammation causes

swelling, which compresses the artery supplying blood to the appendix. Blood

flow protects against bacterial growth, so any reduction aids infection, which

creates more swelling. If the blood supply is cut off completely, bacteria have

free rein until the appendix bursts. A slender appendix is especially

susceptible to this chain of events, so appendicitis may, paradoxically, apply

the selective pressure that maintains a large appendix. Far from arguing that

everything in the body is perfect, an evolutionary analysis reveals that we

live with some very unfortunate legacies and that some vulnerabilities may even

be actively maintained by the force of natural selection.

Evolution of

Darwinian Medicine

Despite the power

of the Darwinian paradigm, evolutionary biology is just now being recognized as

a basic science essential for medicine. Most diseases decrease fitness, so it

would seem that natural selection could explain only health, not disease. A

Darwinian approach makes sense only when the object of explanation is changed

from diseases to the traits that make us vulnerable to diseases. The assumption

that natural selection maximizes health also is incorrect--selection maximizes

the reproductive success of genes. Those genes that make bodies having superior

reproductive success will become more common, even if they compromise the

individual's health in the end.

Finally, history

and misunderstanding have presented obstacles to the acceptance of Darwinian

medicine. An evolutionary approach to functional analysis can appear akin to

naive teleology or vitalism, errors banished only recently, and with great

effort, from medical thinking. And, of course, whenever evolution and medicine

are mentioned together, the specter of eugenics arises. Discoveries made

through a Darwinian view of how all human bodies are alike in their vulnerability

to disease will offer great benefits for individuals, but such insights do not

imply that we can or should make any attempt to improve the species. If

anything, this approach cautions that apparent genetic defects may have

unrecognized adaptive significance, that a single "normal" genome is

nonexistent and that notions of "normality" tend to be simplistic.

The systematic

application of evolutionary biology to medicine is a new enterprise. Like

biochemistry at the beginning of this century, Darwinian medicine very likely

will need to develop in several incubators before it can prove its power and

utility. If it must progress only from the work of scholars without funding to

gather data to test their ideas, it will take decades for the field to mature.

Departments of evolutionary biology in medical schools would accelerate the

process, but for the most part they do not yet exist. If funding agencies had

review panels with evolutionary expertise, research would develop faster, but

such panels remain to be created. We expect that they will.

The evolutionary

viewpoint provides a deep connection between the states of disease and normal

functioning and can integrate disparate avenues of medical research as well as

suggest fresh and important areas of inquiry. Its utility and power will

ultimately lead to recognition of evolutionary biology as a basic medical

science.

The Authors

RANDOLPH M. NESSE

and GEORGE C. WILLIAMS are the authors of the 1994 book Why We Get Sick: The

New Science of Darwinian Medicine. Nesse received his medical degree from the

University of Michigan Medical School in 1974. He is now professor of

psychiatry at that institution and is director of the Evolution and Human

Adaptation Program at the university's Institute for Social Research. Williams

received his doctorate in 1955 from the University of California, Los Angeles,

and quickly became one of the world's foremost evolutionary theorists. A member

of the National Academy of Sciences, he is professor emeritus of ecology and

evolution at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and edits the

Quarterly Review of Biology.