Family Cultures: Unintended

Juxtaposition

By Mike Lavin

The

family plays a crucial role in encultu was

stalwartly pro-Irish as you may expect, that is Irish with a green not an

orange. When I was young, I can remember

the time when our family vacationed in

was

stalwartly pro-Irish as you may expect, that is Irish with a green not an

orange. When I was young, I can remember

the time when our family vacationed in

Since

I already had an appointment with Laura Washington, Director of Communication

at the New York Historical Society, I thought I would take the opportunity and

view their new exhibit entitled “Group

Dynamics: Family Portraits and Scenes from Everyday Life.” Since “family

and community” was the theme of our next volume, I thought it was worth

exploring the family portraiture of early Americans on display.

The

exhibit was an interesting portrayal of how early Americans, mostly New

Yorkers, mostly affluent, perceived themselves. Ninety works were on display,

spanning across colonial through to the Victorian era. I saw cultural definition

through familial and social identity. The clothes they were wearing, the

male-female portrayals (males with books and females with flowers). The eyes reflected optimism, assuredness,

eagerness, happiness, and hope.

I

took a moment out and asked the room assis tant

which painting, according to him, best captured the

spirit of a family. He sat down and talked to me at length. Knowledgeable and

courteous, he first spoke about this exhibition. Then, almost talking to

himself, he commented that, being African American, he finds it too disturbing

to go to the “other” exhibit on that floor. So, off I went in search of this

“other”.

tant

which painting, according to him, best captured the

spirit of a family. He sat down and talked to me at length. Knowledgeable and

courteous, he first spoke about this exhibition. Then, almost talking to

himself, he commented that, being African American, he finds it too disturbing

to go to the “other” exhibit on that floor. So, off I went in search of this

“other”.

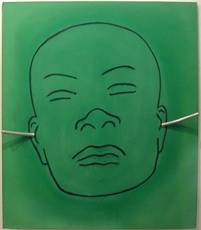

It

was just down the corridor, the other exhibit, entitled “Legacies: Contemporary Artists Reflect on Slavery”. I am quite sure

the museum had no real purpose in juxtaposing these two very different sets of

paintings. However, like the assistant, I did see a connectedness in the direct

contrast, particularly when you looked at the eyes of the portraits. Legacies was the

antithesis of Dynamics. Though it

focused mainly on how slavery fashioned American society, my concern was how

slavery affects the family, how it affects development and socialization.

The

most startling, and disturbing for me, was Lorenzo Pace's sculpture Julani and the Lock Family History Tree,

2004. His work, his family tree, is

studded with icons of slavery, as are the eyes of the family members – all eyes

seem to be in proximity to slave codes such as locks and fences. If you look

closely, you can see a quote from Pace’s five year old daughter, "Daddy,

am I a slave?" The eyes in Compos-Pons' 2003 Replenishing manifests the linkage of pain and sorrow of

hopelessness and despair. So too are the

eyes of Cedric Smith's Runaway Man,

2006. In Queen Nanny: Maroon Series,

2004 by Renee Cox, the rebellious gaze provokes one to explore the historical

roots of suffering.

The corridor between the two

displays is short, but in fact it is immeasurable. One

exhibit manifest families with hopefulness, the other with despair. One with smiles, books, and flowers and the other with shackles,

lynching, and enslavement.

Slavery, even after so many years, appears to linger in one's gene